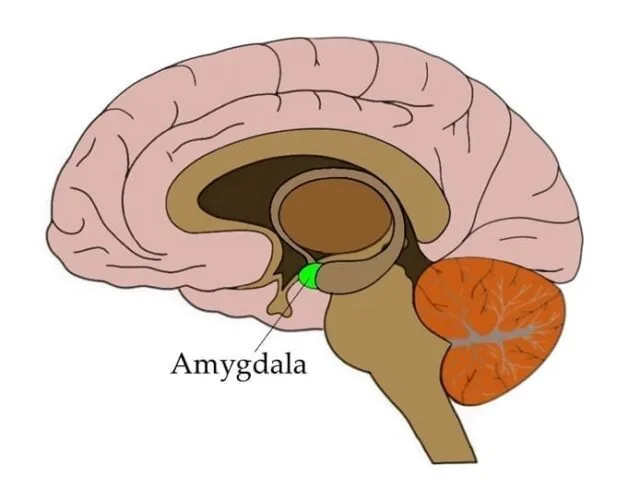

Our brain’s Amygdala, a tiny but magnificent superstar, is located deep among its hidden chambers. This fascinating small structure holds the key to revealing the mysteries of fear, pleasure, and everything in between, like a maestro conducting our emotional symphony. In this blog post, we will explore the captivating functions of the Amygdala and how we can gain control over our emotions through meditation.

A group of nuclei located deep within the temporal lobe make up the amygdala. Because one of the amygdala’s most noticeable nuclei has an almond-like form, the term amygdala, which means “almond,” is derived from Latin. The Amygdala activates when emotions approach, setting off a chain of events that resonate throughout our bodies. This has a significant impact on our blood flow, which serves as our vital pulse.

The Amygdala triggers a fascinating phenomena known as the “fight-or-flight” reaction in times of extreme fear or stress. An instantaneous rush of adrenaline that rushes through our blood and turbocharges our bodies is brought on by this primitive instinct. In response, our blood vessels enlarge, enabling a swift increase in blood flow to our muscles and essential organs, preparing us to face the impending threat or leave at breakneck speed.

It’s interesting to note that research reveals the amygdala might receive information about potentially alarming items in the surroundings before we are even aware that there is anything to be afraid of. The thalamus and amygdala are connected by a pathway, and the sensory data associated with frightful stimuli may travel along this channel to the amygdala before being consciously processed by the cerebral cortex. This enables the start of a fear response before we have a chance to consider what is so frightening. If we are in serious danger, this reflexive response may be helpful.

For instance, you don’t want to have to spend a lot of time thinking about the threat a snake might offer if it darts out at you while you are strolling through the grass. Instead, you want your body to react instantly with dread and jump backward without your conscious command.

One method to produce this kind of response might be the direct connection from the thalamus to the amygdala. In an experiment, the forebrain commissures were purposefully only partially removed in one hemisphere while only the amygdala was excised from the other.

The effect on emotionality in this experiment was particularly dramatic because a normally behaving animal seeing the world through the eye on the side of the amygdalectomized hemisphere was suddenly transformed into an abnormally fearless and docile creature by severing the only remaining interhemispheric connection (the splenium of the corpus callosum) with an implanted suture.

Other than this, On the other hand, when we feel happiness, love, or contentment, the Amygdala once more weaves its entrancing spell. This time, though, it directs us to a condition of tranquilly and relaxation. The moderate stimulation of the amygdala triggers the release of endorphins, the brain’s built-in pleasure chemicals, which widen blood vessels. Because of this, a warm and comfortable flow of blood fills our bodies, filling us with joy and exhilaration.

Now, how to take control of our amygdala? It has been demonstrated that mental exercise in the form of meditation affects how emotions are processed. When someone practices meditation, they often focus their attention or awareness on a single thing—an object, sound, idea, or experience. The most popular type of meditation, attention-based or mindfulness-based meditation, places an emphasis on accepting the “knowing” of in-the-moment experiences while directing attention to an object or a physical sensation (such as breathing). Distracting thoughts or sensations are to be experienced rather than actively suppressed or regulated.

According to one study, meditation experts who have been performing attention and loving-kindness meditation for at least five years (N = 10) have increased amygdala connectivity with the dorsal anterior cingulate, premotor, and primary somatosensory cortices when processing positive emotions in comparison to novices (N = 15) (Leung et al., 2015). Furthermore, short-term mindfulness or compassion meditation training reduces the behavioural and physiological reactions to stress and anxiety (e.g., Hölzel et al., 2010; Pace et al., 2009, 2013; Serpa, Taylor, & Tillisch, 2014), and modifies amygdala activity during emotion processing (Desbordes et al., 2012). This is supported by recent longitudinal studies.

This means that the Amygdala gradually becomes less prone to inciting fear responses and more tuned in to a state of tranquilly with each mindful breath.

We learn to focus our attention away from the disorderly maelstrom of ideas and anxieties that frequently plague our minds by practicing mindfulness through meditation. Instead, we concentrate on the now, which frees us from the control of unfavourable feelings and unpleasant circumstances. Additionally, meditation encourages the production of neurotransmitters that support relaxation and a sense of well-being, such as serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). These molecular alterations establish a peaceful environment within the brain, lowering stress hormones and fostering a feeling of inner tranquilly. You can develop stronger neural connections in your brain by regular meditation practice, which will improve your capacity to control your emotions and react to stressful situations in a composed manner.